The Torah, with its oral interpretation, was taught to Moshe at Sinai. Moshe was instructed to have this explanation passed down orally from one generation to the next. Although it was originally forbidden to teach this oral tradition from a written text, it eventually became necessary to publish the Oral Torah, since circumstances placed it in danger of being forgotten. But even once it was written, it was redacted in a way that would preserve its oral nature.

The Torah, with its oral interpretation, was taught to Moshe at Sinai. Moshe was instructed to have this explanation passed down orally from one generation to the next. Although it was originally forbidden to teach this oral tradition from a written text, it eventually became necessary to publish the Oral Torah, since circumstances placed it in danger of being forgotten. But even once it was written, it was redacted in a way that would preserve its oral nature.

In this article, we will address the skeptic:

What evidence is there that the Oral Torah was given by God at Sinai? Perhaps it is the brilliant product of the Talmudic Rabbis? After all, if God intended for the Torah to be observed in any specific way, why didn’t He just tell us so Himself in the Torah?

Once we have investigated the necessity for, as well as the advantages of, the Oral Torah, we will then turn to a potential serious disadvantage: accidental and/or deliberate distortion of the material. Any message relayed from one person to the next orally and not in writing is prone to distortion, reminiscent of the game “telephone,” which you may have played in your youth. The tendency for messages to be distorted raises the obvious question: Since the Oral Torah was transmitted for dozens of generations from one person to the next, isn’t it at least possible that the version we have today is vastly different than the Torah originally taught to Moshe at Sinai?

This article will address the following questions:

- How do we know that the Written Law was originally transmitted with an oral component?

- What proof to the existence of the Oral Torah can we find in the text of the Torah itself?

- Why do we have an Oral Torah in the first place? Why didn’t God just put the entire Torah in writing?

- What proof is there that the Oral Torah was not simply fabricated by the Sages of the Talmud?

- How can we be sure that the Oral Torah we have today remained true to the original intent of the Torah?

The System of Halachah – Jewish Law

Outline:

Section I. Necessity of the Oral Torah

Part A. Vocalizing and Punctuation

Part B. Seeming Contradictions Within the Text

Part C. Unexplained Laws

Part D. Unexplained Institutions

Part E. Textual References to an Oral Tradition

Section II. Advantages of Having the Oral Torah

Part A. Book Knowledge is Insufficient

Part B. The Oral Torah Resolves Ambiguities of the Written Text Part C. Written Law Can Be More Concise

Part D. Ensures Personal Contact and Feedback Part E. Integration with the Material

Part F. Safe from Theft or Distortion

Part G. Flexibility to Adapt to a Changing World

Section III. Accuracy of the Transmission

Part A. Checks and Balances

Part B. Biblical Verification

Part C. External Verification

Part D. The Covenant

Section I. Necessity of the Oral Torah

How do we know that there is an Oral Torah that interprets the Written Torah and shows how it applies? More specifically, what indication is there that the Oral Torah was transmitted together with the Written Torah rather than being an ex post facto rationalization of the Written Torah’s intent? We will examine five categories of evidence for the Oral Torah.

Part A: Vocalisation and Punctuation

Since the Written Torah does not contain vocalization or punctuation marks, in order to read the text properly a linguistic tradition is necessary. It would be inconsistent (and intellectually dishonest) to accept the linguistic tradition and discard the legal tradition when they are both parts of the same oral tradition.

i. Aleph-Bet

1.Shabbat 31a – Without an oral tradition one does not even know how to read the Hebrew letters!

The Jewish Rabbis taught:

A non-Jew came to Shammai and asked him, “How many Torahs do you have?”

“Two,” he replied, “the Written Torah and the Oral Torah.”

“I believe you about the written one but not about the oral one. Convert me to Judaism on condition that you teach me the Written Torah [only].”

He [Shammai] scolded him and drove him away in disgrace.

The man then came to Hillel, who converted him. On the first day, he taught him, “Aleph, bet, gimel, dalet…” The following day he reversed the order to him.

“But yesterday you did not teach me this way,” the man protested. [Hillel said] “So you see that you must rely upon me? Then rely upon me regarding the Oral [Torah] as well.”

ii. Vocalization and Punctuation Marks

The written Torah scroll does not contain any vocalization or punctuation marks. The system of nekudot (dots indicating vowels) in use today and found in any standard Chumash was developed between the seventh and tenth centuries CE. Until that system of vowels was developed, the only way to accurately read the Tanach (acronym for Torah, Prophets and Writings, i.e. the Hebrew Bible) was to rely on the orally transmitted vowelizing system that had been passed down through the generations.

Aside from enabling the accurate reading of the Torah, the proper vocalization of Hebrew words affects their meaning as well. Hence, of necessity one must rely on an oral tradition simply to understand the elementary translation of the Torah’s text. We will illustrate this point with a discussion of two biblical verses prohibiting the eating of one or two substances with the same Hebrew spelling (בלח). How can we determine what the verses refer to?

1. Shemot 34:26 – The Torah prohibits cooking a goat in its mother’s…

You shall not cook a goat in its mother’s_______. :ֹו ּמ ִאבלחַּביִדְּגל

2. Vayikra 3:17 – It is forbidden to eat any…

[This is] an eternal statute for all your generations, in all your dwelling places: You may not eat any________ or any blood.

The biblical Hebrew word for milk is this context is chaleiv (בֵלֲח), spelled with the consonants chet-lamed-bet. But that is not the only word spelled with those same letters. The word cheilev (בֶלֵח), meaning animal fat, is spelled with the same three Hebrew letters. Does the Torah forbid cooking a goat in its mother’s fat, or her milk? Does it forbid the consumption of all dairy products, or animal fats?

Without an oral tradition we would not know how to read the words in either of these verses.

3. Kuzari 3:35 – If an oral tradition is needed to be able to read the written text, it is certainly needed to understand the text’s meaning.

Simply to know what the words of Moshe’s book are and how to pronounce them, we require a number of transmitted instructions – such as vowelizing, cantillation, sentence endings, and the correct spellings. The need for a tradition about how to explain the meaning and interpretation of the text is obviously much greater, since it is far more extensive than the simple reading of the words!

Part B. Seeming Contradictions Within the Text

A close examination of the Torah’s text reveals many seeming contradictions and textual anomalies. Resolving these difficulties is a significant component of the work of classical Biblical commentators such as Rashi. In fact, any student of Rashi assumes that if there were not some anomaly with the verse at hand, Rashi would not have commented on it! Since the Written Torah is God’s handiwork, it is obviously perfect and flawless. The resolutions of these textual difficulties have been transmitted in an oral tradition.

1.Sefer Mitzvot Gedolot, Introduction – Any statements in the Torah that appear to contradict one another require the explanations provided in the oral tradition.

Had an oral explanation of the Torah not been given, the entire Torah would be totally indecipherable, because some verses [seem to] make no sense or contradict one another.

For example:

“The Children of Israel sojourned in Egypt for 430 years” (Shemot [Exodus] 12:40). We find that Kehat, son of Levi, was among those who originally came to Egypt. If you count the entire lifespan of Kehat – 133 years, the lifespan of his son Amram – 137 years, and add that to the fact that his son Moshe was 80 years old when the Blessed Holy One spoke to him in Egypt, it adds up to only 350 years. (See Rashi to Shemot 12:40)

Likewise, the Torah tells us that seventy people originally came to Egypt. But when you count them, it turns out that there are only sixty-nine. (See Bereishit [Genesis], Chapter 46 and Rashi, Bereishit 46:15)

Also, one verse says, “Seven days shall you eat matzot,” while another says, “Six days shall you eat matzot.” (See Shemot 23:15 and Devarim [Deuteronomy] 16:8)

Also, “You shall count seven weeks,” meaning that one must count only forty-nine days, while another verse says, “Count fifty days.” (See Devarim 16:9 and Vayikra [Leviticus] 23:16)

One verse says, “God descended upon Mount Sinai,” while another says, “You saw that I spoke with you from Heaven.” (See Shemot 19:20 and 20:18)

There are many such examples whose solution becomes clear only through the Oral Torah, which was transmitted through the Sages.

Part C. Unexplained Laws

The Torah makes general reference to many laws without specifying how to observe them. How is brit milah (circumcision) performed? How is a sukkah constructed? What and how does one write on the doorposts of one’s home?

1.Rabbi Yehudah HaLevi, Kuzari 3:35 – Civil law, inheritance law, and even the obligation to pray cannot be derived from the plain text of the Written Torah without an oral tradition.

I wish to see one [who denies the Divine origin of the Oral Torah] judge between two parties according to the rules mentioned in Shemot 21 and Devarim 21. The text of the Torah leaves the rules obscure, and this certainly applies where the plain words themselves are obscure, where we rely totally on the Oral Torah. I would like to see his system of the hierarchy of inheritance as he deduces them from the passage of Tzelophchad’s daughters…or how a circumcision is to be performed, how tzitzit or a sukkah are made. Let him show me the source for the obligation to pray to God.

There are many more examples of such unexplained laws that are only known through the Oral Torah: “self-affliction” on Yom Kippur (Vayikra 23:26, Tractate Yuma 73b) or work (melachah) that is forbidden on Shabbat (Shemot 20:9-10, Tractate Shabbat 73a), and the explanation for “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth…” (Shemot 21:24), etc.

Part D. Unexplained Institutions

The Torah makes reference to a host of social institutions without ever specifying the procedures involved in implementing them. One example is marriage. The Torah lists some of the obligations a husband has toward his wife, but never specifies how a wedding is performed. The procedure for divorce is a bit more explicit, “Write her a book of severance” (Devarim 24:1), but nowhere does it explain what is written in this book.

The Torah talks about Jews’ relationships with a convert to Judaism, but it does not tell us the conversion process. Since legal definitions for these unexplained institutions are required for a functioning society, there must have been an oral tradition to explain them. In all these cases, we need the Torah to give us detailed instructions. The fact that the Written Torah does not tell us how to fulfil these mitzvot is in itself a clear indication that there is an accompanying Oral Torah.

Part E. Textual References to an Oral Tradition

The blatant lack of vital information in the Written Law is not the strongest proof of the existence of the Oral Torah. More compelling is that the Written Torah itself refers explicitly to the Oral Torah in a number of places.

i. Ritual Slaughter (Shechita)

1. Devarim 12:21 – The procedure for the slaughter of livestock is found in the Oral Torah only.

When the place chosen by God to carry His name is far away, you may slaughter your cattle and sheep that God has given you in the manner that I have commanded you. You may then eat them in your cities according to your heart’s desire. If slaughter is to be performed in the manner that I have commanded you, where is it that these commands are written? Such instructions are found nowhere in the Written Torah. This must be reference to an oral tradition that existed already at the time of the giving of the Torah.

2. Kuzari 3:35 – Without the Oral Torah, one does not know the procedure of kosher slaughter.

What is the act of ritual slaughter (of animals)? Perhaps it is merely stabbing or killing in any manner? And why is slaughter performed by non-Jews forbidden? Why is slaughter different from skinning and other actions associated with it?

ii. Construction of the Mishkan (Tabernacle)

1.Shemot 26:30 – Though God showed Moshe how to construct the Mishkan, those details are not recorded in the Torah.

You are to erect the tabernacle according to its rules, as you were shown on the mountain.

Again, God is referring to instructions that were originally given orally – further evidence of the existence of an Oral Torah.

Key Themes of Section I.

We have seen a number of proofs that the Written Torah relies upon an oral tradition and indeed assumes the existence of the Oral Torah. These include:

- The need for vocalization and the existence of seemingly internal contradictions, as well as unexplained laws and institutions.

- As we saw regarding the prohibition of meat and milk, it is impossible to read and understand the words of the Torah without a tradition regarding the vowelizing and punctuation of the words. Simply to read the text correctly requires an oral tradition. Since the same tradition that teaches us the proper reading of the text also instructs us about the concepts and laws, whoever trusts the tradition regarding the vowelizing and punctuation must also accept the entire Oral Torah. It would be inconsistent to accept only part of the oral tradition.

- A close reading of the Torah reveals many seeming contradictions and textual anomalies that beg for explanation, such as how many of Yaakov’s family descended to Egypt, how many years the Jewish people were enslaved there, and how God spoke at Mount Sinai.

- Many of the laws mentioned in the Written Torah are too vague to be understood on any practical level. Mitzvot like brit milah, sukkah, and etrog need to be further clarified in order to be applied. Furthermore, some of the mitzvot have self-declared high stakes for reward (e.g., honoring parents) and accountability (e.g., Yom Kippur), so it is logical to assume their observance will be clarified in the Oral Torah.

- Other laws written in the Torah, such as Shechitah and the construction of the Mishkan, assume background information which the Written Torah does not supply but hints to. Here the Torah clearly reveals to us that it is relying upon oral explanation.

Section II. Advantages of the Oral Torah

We have explained what the Oral Torah is and demonstrated proof for its existence. What must also be explained, however, is the absolute necessity for the Torah to exist as an oral tradition. Why didn’t God just write the entire Torah down? What are the advantages of giving some information in writing while keeping other information oral?

Part A. Book Knowledge is Insufficient

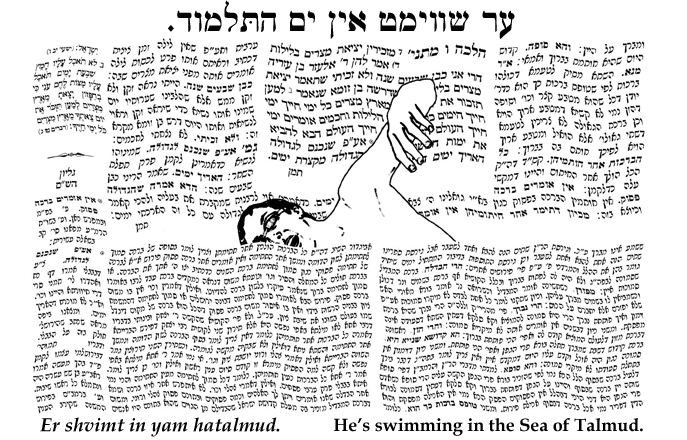

Almost all systems of education rely on oral transmission. Think about how people learn to perform surgery or train to be electricians. There are many skills that people cannot just learn out of a book. Rabbi Lawrence Kelemen demonstrates this point poignantly. He asks his class, “Who here knows someone who learned how to swim from a book?” When no hands pop up, he points out the obvious reason: “Tragically, all those people who learned how to swim from a book are no longer with us today.”

Similarly, observing mitzvot requires some form of experiential knowledge as well.

1.Otzar HaMidrashim, Tzedakot, pg. 499 – One can learn more from seeing the Torah lived than by reading about it out of a book.

Serving Torah [scholars] is greater than studying Torah, as we find regarding Yehoshua. It says, “Yehoshua ben Nun, Moshe’s attendant, replied” (Bamidbar 11:28) – it does not state here “Moshe’s student” but “Moshe’s attendant.”

What did he do to serve him? He would carry the bucket and [bathing] utensils and bring them for him to the bathhouse. Furthermore, some laws cannot be learned from a book.

Here is an example of one such law about kosher meat.

2.Shulchan Aruch/Rema, Yoreh Deah 64:7 – The laws of preparing kosher meat require mentorship.

The method of removing these forbidden fats must be learned by observing an expert in the field; it is impossible to explain it sufficiently in a book.

Part B. The Oral Torah Resolves Ambiguities of the Written Text

To further illustrate why an oral accompaniment to written laws is so critical, let’s focus for a moment on the ongoing debate over the interpretation of the Second Amendment of the US Constitution. This law, regarding the right to bear arms, was passed in 1791. The debate focuses on whether that right rests only with the State (such as the police or an army) or applies also to private individuals.

1. Gun Control, Nytimes.com, January 14, 2011

Recent battles have taken place in the courts, revolving around fundamentally differing interpretations of the oddly punctuated, often-debated Second Amendment, which reads: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

A 1939 decision by the Supreme Court suggested, without explicitly deciding, that the Second Amendment right should be understood in connection with service in a militia. The : “collective rights” interpretation of the amendment became the dominant one, and formed the basis for the many laws restricting firearm ownership passed in the decades since. But many conservatives, and in recent years even some liberal legal scholars, have argued in favor of an “individual rights” interpretation that would severely limit government’s ability to regulate gun ownership.

The Supreme Court in 2008 embraced the view that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to own a gun for personal use, ruling 5 to 4 that there is a constitutional right to keep a loaded handgun at home for self-defense. But this landmark ruling addressed only federal laws; it left open the question of whether Second Amendment rights protect gun owners from overreaching by state and local governments.

How would you interpret the Second Amendment?

If you support the right of individuals to own guns, you would cite, “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

If you opposed the right of individuals bearing arms, but required the state to bear arms, you would quote, “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State (but not private citizens).

In light of the potential ambiguity of written laws, an oral law clarifies the intent and application of the laws.

2. Rabbi Yosef Albo, Sefer Ha’Ikarim 3:23 – The meaning of a text can always be misconstrued.

Any written text…can be interpreted in two opposing ways…and a written explanation would then need another explanation ad infinitum. This is what happened to the Mishnah, which is an explanation of the Written Torah…[and later required a further explanation – the Gemara – to resolve its ambiguities.]

Part C. Written Law More Concise

The fact that an oral tradition resolves the vagueness of a written text raises a burning question: why didn’t God just give a lengthier and clearer text for the Torah? Since God could certainly have written a perfect text, we must conclude that the uncertainties in the Torah serve a purpose. Indeed, the ambiguity of the written text facilitates its depth and allows for multiple levels of meaning. Writing out every detail of information that can be garnered from the Torah would make it a very cumbersome text indeed!

1.Talmud Bavli, Eruvin 21b – One cannot write out everything implied in such a multifaceted text as the Torah.

Lest you ask, “Since the laws [contained in the Oral Torah] are important, why were they not written?” For this the verse states, “The making of books is endless” (Kohelet – Ecclesiastes 12:12).

Part D. Ensures Personal Contact and Feedback

A written text requires no personal contact in the learning process. An oral tradition, on the other hand, requires the give-and-take of dialogue, ensuring that the student has a relationship with the transmitter of the tradition and that the teacher has feedback from the student.

1.Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan,2 Handbook of Jewish Thought pg.179 – Verbal transmission ensures clarity in a way that no text can achieve.

The Oral Torah was originally meant to be transmitted by word of mouth. It was transmitted from master to student, so that if the student had any question, he would be able to ask and thus avoid ambiguity. A written text, on the other hand, no matter how perfect, is always subject to misinterpretation.

Part E. Integration with the Material

The intensive process of Talmudic study enables the student to assimilate and integrate the Torah.

1.Maharal, Tiferet Yisrael, Chapter 68 – Since the Oral Torah requires concentration and memorization, it becomes completely integrated into a person.

Since the Oral Torah is spoken, the Torah becomes completely integrated within the person; it is not something written on a parchment…and detached from the student, rather it becomes part of the person. The Oral Torah is the covenant, the bond that joins two sides together – the Giver of the covenant and the receiver. It [the covenant] could not be the Written Torah, since it is not integrated within the person. That is why God made a covenant with the Jewish people only through the Oral Torah, as it says “According to these words have I made a covenant with you” (Shemot 34:27; Gittin 60b).

Part F. Harder to Steal or Distort

Another advantage of having an oral tradition is its capacity to guarantee that the true meaning of the Torah remain exclusively with those who are committed to keeping it.

1. Hoshea (Hosea) 8:12 – What would happen if the secrets of the Torah were made public? If I would write for them the many facets of My Torah, they would be regarded like a stranger (i.e., non-Jew).

The Sages interpreted this verse as follows:

2.Talmud Yerushalmi, Pei’ah 13a – If the entire Torah had been written, there would be no difference between Jew and non-Jew.

Rabbi Avin said: Had I written the many facets of My Torah, wouldn’t they be considered like strangers? What [would be] the difference between them and other nations – these could display their books and those could display their books, these could display their records and those could display their records?

3. Yalkut Shimoni, Parashat Ki Tisa 405 (end) – The Oral Torah preserved the uniqueness of the Jewish nation even while in exile.

When God came to give the Torah, he told Moshe of the Scriptures, Mishnah, Aggadah and Talmud, all in order, as it says “God spoke all of these words” – including the questions that each mature student would ask his teacher in the future. God said to him: “Go and teach this to the people of Israel.” Moshe replied: “Master of the Universe, write it down for your children.”

Whereupon He said: I would have liked to give it to you in written form, but I know that in the future the nations will rule over them and will take the Torah from them. My children would then be no different than the other nations of the world. Therefore, I shall give them the Scriptures in writing, but [I will give] the Aggadah, Mishnah and Talmud in oral form. God said to Moshe, “Write for yourself” – the Scriptures – but through the Mishnah and Talmud there will be a distinction between Israel and the nations.

4.Rabbeinu Bachya, Commentary to Shemot 34:27 and citing the above Midrash – God did not want the ones who refused to accept the Torah to be able to understand it on the same level as the Jews.

It appears to me that the reason Moshe was not given permission to write down the Mishnah is because if he had, the secrets of the Written Torah would be revealed, and then all the other nations who neither accepted nor wanted the Torah would understand it as well as the Jews.

Part G. Flexibility to Adapt to a Changing World

When the Torah was given on Mt. Sinai, there were no democracies, computers, nuclear warheads or universities. How does the Torah relate to a dynamically changing world?

As we pointed out in the third class in this series, the Oral Torah consists of a system of principles for applying the Torah to new situations as they arise.

1.Midrash Shemot Rabbah (Vilna) 41 – Moshe was taught the general principles of how to apply the Torah to any situation that might arise in the future.

Did Moshe really learn the entire Torah (from God)? But, as the verse attests, “its breadth is wider than the Earth” (Iyov/Job 11), and he learned it in only forty days?! Rather, God taught Moshe the principles.

2.Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, Handbook of Jewish Thought, Volume I, pg. 179 – The Oral Torah is meant to cover every possible case.

The Oral Torah was meant to cover the infinitude of cases which would arise in the course of time. It could never have been written in its entirety. It is thus written (Kohelet/Ecclesiastes 12:12), “The making of books is endless.” God therefore gave Moses a set of rules through which the Torah could be applied to every possible case.

3.Based on Rabbi J. David Bleich, Contemporary Halakhic Problems I & III, Ktav Publishing House, p. xiv. – The Torah was entrusted to man to address any possible situation.

Although the Torah is immutable, the Sages teach that the interpretation of its many laws and regulations is entirely within the province of the intellect. Torah is Divine but “lo ba-shamayim hi – it is not in the Heavens” (Deut. 30:12); it is to be interpreted and applied by man…Man is charged with the interpretation of the text, resolution of doubts, and application of the provisions of its laws to novel situations.

The contemporary problems that arise – and their resolution – testify to the vibrant and dynamic nature of the Torah. Technological advances and changing social institutions have given rise to issues that could not possibly have been confronted by rabbinic authorities of preceding generations.

Although contemporary halachic authorities apply Jewish law to cases that could not have been fathomed in the past, nevertheless they do so based on principles and precedents already laid down by the Talmud and its commentators or from the responsa literature.

Key Themes of Section II.

- There are many advantages that an oral tradition has over a written text. First, it overcomes the ambiguity inherent in any written document by necessitating the teacher to explain himself to his students.

- The oral mode of transmission also fosters clarity by promoting the teacher-student relationship.

Additionally, the demands of memorizing an oral tradition ensure that the material is ingrained deeper into those who learn it.

- The oral tradition also ensures that the true interpretation of the Written Torah will remain uniquely in the hands of the Jewish people, to whom God gave it in the first place, ensuring Jewish identity in exile.

- The Oral Torah enables the rabbis to address societal and technological changes throughout history.

Section III. Accuracy of the Transmission

As demonstrated above, the written Torah must have been given with an oral component. We must now address the following question: how do we know that the Oral Torah as presented in the Mishnah and Talmud is a faithful transmission of the original Oral Torah?

Those who question the authenticity of the Oral Torah claim that it was an invention of “the Rabbis” who authored the Mishnah and Talmud, not a tradition dating back to Sinai. How can we refute such a claim? What proof is there that these texts are really a record of an ancient oral tradition?

Furthermore, the Oral Torah was handed down through forty generations from Moshe to Rav Ashi, the chief editor of the Talmud Bavli; how can we be confident that nothing was lost or distorted along the way? Aren’t all verbal messages distorted by the “telephone game” effect? What makes the Oral Torah different?

In this section we shall describe the steps taken by the carriers of the Oral Torah to guarantee an accurate transmission. We will then illustrate this accuracy through examples from Jewish and non-Jewish sources.

Part A. Checks and Balances

To ensure the accurate and faithful transmission of the Oral Torah, the Prophets and Sages employed a system that protected it from distortion. Four aspects of this system are:

(1) incentive, (2) semichah, (3) yeshiva, and (4) private notes.

i. Incentive

Our Sages took the responsibility for receiving and transmitting the Torah very seriously. They mandated that, in light of the great stakes, this crucial task must be performed correctly.

1. Mishnah, Avot 2:14 – The great reward for Torah study.

Rabbi Elazar said: Be diligent in your Torah study, so you will know how to answer a scoffer. Realize for Whom you are toiling, for your Employer can be trusted to pay you in full for your labor.

2. Ibid. 3:8 – Severe warning not to forget the Torah one has learned.

Rabbi Dostai, son of Rabbi Yannai, said in the name of Rabbi Meir: Anyone who forgets even a single word of his studies is considered by the Torah as equal to someone who has incurred the death penalty.

3. Ibid. 3:11 – It is a serious crime to issue false legal rulings.

Rabbi Elazar of Modi’in said: Someone who makes false interpretations of the Torah – has no share in the World to Come, even if he has the merit of extensive Torah study and good deeds.

4. Ibid. 4:13 – Mistakes in Torah learning are like intentional transgressions.

Rabbi Yehudah said: Be careful to ascertain the correct version as you study, for an error in one’s learning is considered to be a premeditated transgression. The great reward for Torah study and the dire consequences of its neglect provided both the positive and negative motivation, respectively, for the accurate transmission of the Oral Torah.

ii. Semichah

Another check on the process of transmission was the institution of Semichah (Rabbinic ordination). In order to be authorized to render halachic decisions or to carry the tradition on to the next generation, a scholar had to be ordained by someone from the previous generation who himself was ordained in this manner. Hence, only those who had proven themselves worthy of this ordination were trusted to pass the tradition further.

1.Rambam, Hilchot Sanhedrin 4:1 – The process of Semichah started with Moshe Rabeinu and continued from teacher to student throughout the generations.

At least one of the members of the Supreme Sanhedrin (High Court), a minor Sanhedrin, or a court of three judges must be ordained by someone who was ordained himself.

Our teacher, Moshe, ordained Yehoshua (Joshua) by placing his hands upon him, as Numbers 27:23 states: “And he placed his hands (samach) upon him and commanded him.” Similarly, Moshe ordained the seventy judges, and the Divine Presence rested upon them. Those elders ordained others, who ordained others, etc. Therefore, it turns out that whoever is ordained can trace his status back to the time of Yehoshua’s court and even to the court of Moshe our teacher. It makes no difference whether a person is ordained by the president of the Sanhedrin or by an ordained scholar who never became a member of a Sanhedrin.

After the completion of the Mishnah, the Jewish communities in the Land of Israel dwindled dramatically. In ever increasing numbers, the scholars left for safer communities in other countries, mainly Babylon (Iraq). Since a scholar could be ordained only in the Land of Israel, eventually, during the fourth century, the chain of ordination came to an end. It will be renewed only after the arrival of the Messiah. Despite the cessation of the formal institution of Semichah, the Jewish community has accepted the authority of rabbis through each generation until today.

iii. Yeshiva

Additionally, in every generation, the Oral Torah was passed on to the next by far more than one individual. Every generation had its yeshiva or yeshivot, academies of learning in which the teachings of the Oral Torah were reviewed and scrutinized.

1.Rambam, Introduction to Mishnah Torah – Every leader passed on the oral tradition along with “his court.”

“The mitzvah,” meaning the explanation of the Written Torah, he (Moshe) did not write down. Instead, he commanded it [verbally] to the elders, to Yehoshua, and to the entire nation of Israel, as the verse states: “Be careful to observe everything that I prescribe to you” [Devarim 13:1]. For this reason, it is called the Oral Law.

Even though the Oral Law was not written, Moshe, our teacher, taught it in its entirety in his court to the seventy elders. Elazar, Pinchas, and Yehoshua received the entire tradition from Moses. [In particular, Moshe] transmitted the Oral Law to Yehoshua, who was his [primary] disciple, and instructed him regarding it. Similarly, throughout his life Yehoshua taught the Oral Law in the same oral forum. Many elders received the tradition from him. Eli received the tradition from the elders and from Pinchas. Samuel received the tradition from Eli and his court. David received the tradition from Samuel and his court.

iv. Notes

1.Rambam, Introduction to Mishnah Torah – Even though the Oral Torah was taught orally, every student could write his own private notes of what he had been taught.

Each student was permitted to write, to the best of his ability, personal notes on explanations of the Torah and its laws, as he had heard, as well as the new matters that developed in each generation, which had not been received by oral tradition but had been deduced using one of the Thirteen Principles for Interpreting the Torah and had been ratified by the Supreme Rabbinical Court. This was the practice until the time of Our Holy Rabbi [Yehudah HaNasi].

Rabbi Lawrence Kelemen once set out to prove the authenticity of the Oral Torah by means of an experiment. He tested the Oral Torah’s system of checks and balances against the “telephone” effect. To do this, he started out dividing an entire convention of NCSY youth into groups of twelve for a game of telephone. The first person in line was given a message to secretly pass on to the next person in line, and so on. When the message finally got to the end of each group, his findings were startling. One-hundred percent of the groups got the message totally inaccurately!

But that did not deter Rabbi Kelemen; it only bolstered him. He ran the game again – only this time he introduced an incentive: $100 to any team that accurately transmitted the message. With this incentive, Rabbi Kelemen was able to bring the accuracy up to ninety-five percent!

On a separate occasion, Rabbi Kelemen convened a group of highly motivated Orthodox high-school girls who had gone to Israel for a summer program of intensive learning called Michlelet. For a start, Rabbi Kelemen made the message much more complicated than it had been for the NCSY kids. But he also instituted a system of checks and balances. To instill a sense of initiative, he told the girls that they were going to be taking part in an experiment to prove the veracity of the Oral Torah, and that if they failed they would be making a huge Chillul Hashem, desecration of God’s name (several girls backed out immediately). This time Rabbi Kelemen introduced the element of “Semicha” in that each girl was only allowed to pass on the message once she received confirmation from the person who had taught it to her. He further instituted “yeshiva” in that he had every person from each group of the same “generation” convene to discuss the message before they passed it on to the next “generation.” Rabbi Kelemen did not introduce the use of written notes, for that would have made it too easy.

Still, with these checks and balances in place, Rabbi Kelemen and the girls of Michlelet beat the system: every group transmitted the message with one-hundred percent accuracy!

Part B. Biblical Verification

There are many laws contained in the Mishnah and Talmud that can be historically verified by cross- referencing them with passages in the Prophets and Writings. There are many such proofs to the authenticity of the Oral Torah, but for the sake of brevity we will cite two: the first regarding Shabbat, and the second on prayer.

i. Carrying on Shabbat

One of the prohibitions of “work” on Shabbat is carrying an object from one domain (public or private) to another domain. Though carrying on Shabbat is never mentioned explicitly in the Written Torah as a prohibition, the Oral Torah teaches that there is a source in the Written Torah.

1.Shabbat 96b – The source for the prohibition of carrying on Shabbat is learned from Moshe’s pronouncement to stop bringing donations for the Mishkan (Tabernacle).

Where is the prohibition of carrying something out (of one’s domain on Shabbat) written in the Torah? Rabbi Yochanan said that it comes from the following verse: “Moshe commanded, and it was announced throughout the camp, [‘No man or woman may perform the labor of donating for sacred purposes.’ The people stopped bringing.”] )Shemot 36:6

Where was Moshe stationed? In the camp of the Levites, which was a public domain, and he said to the people of Israel, “Do not carry things from your private dwellings into the public domain.” We have thus found a source for the act of carrying out; but from where do we know about the act of carrying in? It is common logic! In either direction it is the act of transferring from one domain to another, so what difference does it make whether one carries out or carries in?

Note that the Written Torah does not make an explicit statement of the prohibition, nor is it even clear from the text that Moshe was speaking about Shabbat day! Nevertheless, the Oral Torah explains this to mean that there is a prohibition to carry on Shabbat.

We can find verification that this law was observed in the era of the Prophets.

2.Yirmiyahu (Jeremiah) 17:21-22 – Yirmiyahu chastises the nation for desecrating Shabbat by carrying.

God spoke the following: Watch over your lives and do not carry any burden on the Sabbath day or bring anything through the gates of Jerusalem. You must not carry anything out from your houses on the Sabbath day, and you must not perform any labor. You must sanctify the Sabbath day as I commanded your ancestors.

Hence, we see that this prohibition is one that is found only in the Talmud; a reading of the Written Torah does not even hint at such a law. Yet, it was known and practiced before the Talmudic era, in the times of the Prophets. Clearly, it was not fabricated by the Talmudic Sages.

ii. Prayer – Praying for One’s Needs and Giving Thanks to God

The Torah requires us to build a relationship with God through prayer.

1.Rambam (Maimonides) Hilchot Tefillah (Laws of Prayer), 1:1 – The connection of prayer to Avodah is derived in the Talmud as the service (Avodah) of the heart.

It is a positive commandment to pray each day as it is stated, “And you shall serve the Lord your God” (Shemot 23:25)…They taught that “Avodah,” means prayer, as it is stated “And you shall serve Him (le’avdo) with all your hearts” (Devarim 11:13). The Sages asked, “What is the service of the heart? This is prayer” (Ta’anit 2a).

We find an important episode from the Ketuvim (Writings) that demonstrates that prayer was practiced by the prophet Daniel well before the redaction of the Talmud. Just prior to the destruction of the First Temple by Nebuchadnezzar, King of Bavel (Babylonia), he exiled some of the finest Jewish sages and prophets to Bavel.

One night, Nebuchadnezzar had a dream which disturbed him, but which he could not in fact recall. He demanded of all his wise men to tell him the dream and its interpretation. When no one could help him, he decreed that all the sages in Bavel, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, should be killed. Daniel requested from the king, and was granted, additional time to relay the dream. He went home and prayed to God for Divine assistance to shed light on the king’s dream. He was answered, and he then thanked God for saving him and the other sages.

2. Daniel 2:17-19 – Daniel prays to God, is answered, and then thanks Him.

Then Daniel went home to inform his friends Chananiah, Mishael, and Azariah about what had transpired and to pray to God for mercy to reveal the secret of the dream, so he and his companions would not be killed with the sages of Bavel. Then in a prophecy at night the secret was revealed to him. Daniel then blessed the God of Heaven…

A third illustration of how the prophets corroborate the existence of the Oral Law is found below in Part C, External Verification, regarding identifying the day when the Omer offering was brought, the beginning day for the mitzvah of Sefirat Ha’Omer.

Part C. External Verification

In addition to what can be gleaned from the Tanach about the existence of the Oral Torah in ancient times, we can find external verification as well, in other ancient texts and artifacts.

i. The Septuagint

The Septuagint is the first Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, a work initiated in Egypt during the third century BCE. The story of its origin is related in the Talmud (Megillah 9a-b). The Greek ruler of Egypt, Ptolemy II Philadelphus (281-246 BCE), ordered seventy Jewish scholars, whom he brought from Jerusalem, to each translate the Torah. The Talmud relates that a miracle occurred and all seventy translations turned out to be identical. Although the existing versions of the Septuagint (from the Greek word for seventy) have changed much over time, they still contain some Biblical translations that corroborate with the Oral Torah.

One such translation that required the input of the Oral Torah is the mitzvah of the Omer Offering. The Omer offering is a specified amount of ground barley that was offered by a Kohen (priest) in the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. Only once the procedure for this offering had been completed was it permissible to eat from the newly harvested grain. Counting the days from the day it was offered until the festival of Shavuot constitutes the mitzvah of Sefirat HaOmer (Counting the Omer). The Torah does not give a specific date for bringing this annual offering. It states only that it is to be brought “the day after Shabbat,” and that we are to count seven weeks, or forty-nine days after that, until Shavuot. The Torah likewise does not specify any date for the festival of Shavuot; it is always determined in this manner. In the second century BCE, the determination of this date became the subject of a major debate, challenging the legitimacy of the Oral Torah. But as we shall see, external verification – both in Tanach and elsewhere – supports the Oral Torah’s understanding of this mitzvah.

After relating the law of Pesach, the Torah goes on to relate the laws of the Omer offering and the festival of Shavuot that takes place seven weeks later. But when exactly is the Omer to be offered?

1.Vayikra 23:10-11 – The Torah tells us that the Omer is to be offered “on the day after the Shabbat.”

“Speak to the people of Israel and say to them: When you come to the land that I am giving you and you reap its harvest, you must bring an omer of your first harvest to the priest. He shall wave it (as a wave offering to God), in a manner that will be acceptable to God for you. The priest shall make this wave offering on the day after the Shabbat.”

According to the above, when is the Omer offering to be brought by the Kohen? When is “the day after the Shabbat”? Without the Oral Torah one might assume that it means the first Sunday after the beginning of Pesach (Passover), or perhaps some other Sunday.

The Sadducees, a group of Jews who denied the Divine origin of the Oral Torah, insisted that this verse refers to the first Sunday after the beginning of Pesach. According to the Oral Torah, however, the term “Shabbat” in this verse refers to first day of the Festival of Pesach itself. The term Shabbat can refer to any day in which the Torah forbids labor, whether it is what we normally call Shabbat or any of the festivals listed in the Torah.

In this case, the Torah is telling us to bring the Omer on the second day of Pesach, whichever day of the week that happens to be.

2. Menachot 66a – “Shabbat” refers to the festival day of Pesach.

Rabbi Yossi says: “On the day after the Shabbat” means the day after the Festival. You say that it means the day after the Festival, but perhaps it really means the day after the Sabbath of Creation (the seventh weekday)? But can you

really suggest that? Does the Torah state, ‘The day after the Sabbath that occurs during the Passover week’? It merely says, ‘On the day after the Sabbath’; The year is filled with Sabbath days, so go figure out which Sabbath is referred to.”

Since the “Sabbath” in question is unidentified, it cannot be referring to the weekly observed “Sabbath of Creation” because if it did, we would have no idea which Shabbat it was referring to. Therefore, says the Talmud, it makes more sense to read the verse as referring to a Sabbath-like day, i.e. the festival of Pesach itself. This interpretation is confirmed by a verse in the Prophets:

3.Yehoshua (Joshua) 5:11 – The people ate from the new grain, which is allowed only after the offering of the Omer, on the day after Pesach.

They ate the produce of the land the day after Passover, matzo and roasted grains on that very day.

4. Rabbi Levi ben Gershon (Ralbag), Commentary to Yehoshua 5:11 – The verse in Yehoshua proves the Oral Law’s interpretation of “the day after Shabbat.”

The verse (in Yehoshua) tells us this (that they ate of the produce of the land) because the new grain had been forbidden for them to eat until the day after Pesach. This is a proof that the Torah’s statement that “the priest shall make this wave offering on the day after the Shabbat” refers to the day after Pesach, the 16th of Nissan, and not the day after the Shabbat of Creation, as the Sadducees proclaimed.

The Septuagint’s translation predates both the Sadducees (who denied the Divinity of the Oral Torah) as well as the Mishnah. The Septuagint’s translation concurs with the quote from Yehoshua 5:11 above, corroborating the Oral Torah’s reading of “the day after Shabbat.”

5.Albert Pietersma, A New English Translation of the Septuagint (Oxford University Press, 2009), Leviticus 23:4-11 – The translation of the Septuagint follows the Oral Torah’s interpretation of the word “Shabbat” as the first day of Passover.

These are the feasts to the Lord, holy convocations, which ye shall call in their seasons. In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month, between the evening times is the Lord’s Passover. And on the fifteenth day of this month is the feast of unleavened bread to the Lord; seven days shall ye eat unleavened bread. And the first day shall be a holy convocation to you: ye shall do no servile work. And ye shall offer whole-burnt-offerings to the Lord seven days; and the seventh day shall be a holy convocation to you: ye shall do no servile work. And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, “Speak to the children of Israel, and thou shalt say to them, ‘When ye shall enter into the land which I give you, and reap the harvest of it, then shall ye bring a sheaf, the first-fruits of your harvest, to the priest; and he shall lift up the sheaf before the Lord, to be accepted for you. On the morrow of the first day the priest shall lift it up.’”

The term “the first day” is clearly a reference to the first day of the holiday of Pesach (Shabbat is called “the seventh day,” never the first day). Hence, we see that the Septuagint also confirms the Oral Law’s reading of the Torah.

ii. Josephus

Josephus, or Yosef ben Matityahu as he is known in Hebrew, was a First Century Jewish historian. Josephus was a Hellenized Jew and aligned himself with Rome to save his life, and his writings were sponsored by the Roman leaders (Vespasian and Titus), who destroyed the Second Temple. His writings provide us with historical evidence as to the accuracy of the Oral Torah.

The Torah tells us to take a pri eitz hadar, the fruit of a beautiful tree, together with the lulav (palm branch) on Sukkot. The Oral Torah identifies this term as referring to the etrog, or citron fruit. Josephus, in recording an incident involving Alexander Yannai (King of Judea from 103 BCE to 76 BCE ), confirms that indeed it was the etrog that Jews used to perform this mitzvah in ancient times.

1. Josephus, Antiquities 12:13:5 – Alexander Yannai was pelted with etrogs.

As to Alexander [Jannaeus (Yannai)], his own people were seditious against him; for at a festival which was then celebrated, when he stood upon the altar, and was going to sacrifice, the nation rose upon him, and pelted him with citrons [which they then had in their hands, because] the law of the Jews required that at the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot) everyone should have branches of the palm tree and citron tree; as we have elsewhere related…

It should be noted that this incident is also recorded in the Talmud (Sukkah 48b), composed more than five hundred years later!

Importantly, Josephus also sheds light on the overall acceptance of the Oral Law. Circa 250 BCE two disciples of the leading Sage, Antignos of Socho, rebelled against the authenticity of the Oral Torah and established two groups – the Sadducees and Boethusians. The majority of Jews, known as the Pharisees, remained loyal to the Oral Torah. Josephus observes that the majority of Jews supported the oral accompaniment to the Written Torah (referred to below as the Laws of Moses).

2. Josephus, Antiquities 13:10:6 – The majority of Jews adhered to the Oral Torah.

…[T]he Pharisees have delivered to the people a great many observances by succession from their fathers, which are not written in the Laws of Moses; and it is for that reason that the Sadducees reject them and say that we are only to consider those in the written word as binding, but not to observe those derived from the tradition of our forefathers. And these are the matters over which have arisen great disputes and differences among them, while the Sadducees are able to persuade none but the rich, and do not have popular support, but the Pharisees have the multitude on their side.

iii. Other Ancient Artifacts and Texts

Artifacts predating the redaction of the Mishnah, such as synagogues, mikveh pools and stone utensils conform to the specifications listed in the Talmud.

1.Rabbi Yosef Back, Lecture on Archaeology and the Torah – Archaeological evidence that the Oral Law was known and practiced prior to redaction of the Mishnah.

We have many examples in archeology that demonstrate that the oral law was known and practiced before the redaction of the Mishnah, which took place during the Second Century CE.

- The Written Torah establishes marriage as a mitzvah but does not explain how marriage is accomplished or what responsibilities the spouses assume in the marriage. The Oral Law includes two tractates, Kedushin (sanctification) and Ketubot (marriage contracts), which address the marriage process, marital responsibilities of husband and wife, as well as the content of the marriage contract text of the Ketubah itself. An ancient Ketubah was discovered among the Elephantine Papyri, a collection of Jewish manuscripts dating from the 5th century BCE. They come from a Jewish community at Elephantine, then called Yeb, an island in the Nile at the border of Nubia (also known as Cush – see Megillat Esther 1:1). Yeb was founded approximately 650 BCE during Menashe, the King of Yehuda’s reign. The Ketubah belonged to a woman called, Mibtahiah, and is dated October 14 (24 Tishrey), 449 BCE. This document shows that a Ketubah was used nine hundred years before the Talmud was codified.

- The obligation to read the Torah in public on Shabbat and on Mondays and Thursdays is a rabbinical institution enacted by Moshe Rabbeinu. (See Rambam, Hilchot Tefillah 12:1). The Theodotus inscription dated to the early First Century CE, is a dedication plaque commemorating a Jerusalem “synagogue that was built for the reading of the Torah and the teaching of its commandments.” This shows that the Torah was being read in synagogues in accordance with the Oral Law over two thousand years ago, and over 1,300 years after Moshe instituted the enactment.

- The ancient city of Gezer was located in the coastal plain of Israel, southwest of Jerusalem. Archeologists have unearthed at least eleven stones imbedded in the outskirts of the site, each one with the inscription “Techum Gezer” (Boundary of Gezer) etched in Hebrew and Greek (there were many Greek-speaking Jews at that time). Archeologist Ronny Reich dates these stones to the time of Shimon the Hasmonean who, according to the book of Maccabees I, 13:43-48, re-conquered this city from the Greeks. Shimon died in the year 135 B.C.E., meaning that these stones predate the writing of the Mishnah by 325 years. These stones surround the border of the ancient city at distances ranging from 1,200 meters to 2,000 meters. The halachic techum of a city regarding Shabbat observance is 2,000 amot, cubits – approximately one kilometer (Sotah 27b). Although some of these rocks seem to be much further than the techum Shabbat; the halachah teaches us to measure the techum, not necessarily from the city wall but from the last house built on the outskirts of the town, even though it is outside of the wall (Eiruvin 21a; Shulchan Aruch 398:6). This can explain why in different places the marker stones are found at varying distances from the city walls. The discovery is empirical evidence that the halachah of techum Shabbat was known and observed before the Mishnah was written down.

- Mikveh pools are another example. The Torah states that a person who has become ritually impure can purify himself only by immersing in a mikveh. According to Torah law, a collection of rainwater or water from a subterranean source could be used as a mikveh. The Oral Law (see Mishnayot Mikvaot) adds three conditions: (1) the mikveh must be built into the ground;

(2) the water has to collect in the mikveh without ever having been in a container of any sort; and (3) in order for the mikveh to be fit for people to immerse in it, it must contain at least 40 se’ah (455 liters/ 120 gallons) of such water. Once that volume is collected, any amount of water in containers may be added to it. Throughout the land of Israel, archeologists have discovered hundreds of mikva’ot constructed in accordance with these parameters and predate the Mishnah by over a century.

- According to the Mishnah (Keilim 10:1) stone utensils cannot become ritually impure. This made them ideal and convenient in Jewish society where laws of ritual impurity were observed strictly. In most non-Jewish societies during Biblical times and afterward, utensils were almost always made of wood, earthenware, metal and leather. Stone vessels found uniquely in the remains of Jewish habitations, have been unearthed at dozens of Second Temple period sites throughout the land of Israel, demonstrating that the use of such utensils was widespread long before these rules were codified in the Mishnah.

- The laws governing burial of the dead are found in the Oral Torah (see Sanhedrin 46b). For example, it is necessary to bury the dead outside the city to enable the residents to avoid contact with the ritual impurity present in the graves. This practice has been demonstrated extensively by archeologists. In fact, one litmus test employed by archeologists in Israel to determine whether or not a settlement was Jewish is to find where they located the town cemetery!

- As we learned previously, the Torah commands us to take the fruit of an “eitz hadar, tree of splendor” (Vayikra 23:40), as one of the “Four Species” on Sukkot. The Talmud (Sukkah 35a) concludes that the “pri eitz hadar” is the etrog (citron fruit). During the Great Rebellion just prior to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, the Jews minted coins featuring a representation of an etrog. These coins, which have been found throughout Greater Jerusalem, were in use more than a century before the redaction of the Mishnah.

Part D. The Covenant

The final feasible argument underscoring that the tradition of the Oral Torah which we have in our possession today is accurate is the following: Since we know that God gave the Jews the Written Torah and Oral Torah with the goal of observing the mitzvot, the only way to properly keep the Torah is with the accurate transmission of the oral tradition. God Himself promised that the system will remain intact!

1. Yeshaya (Isaiah) 59:21 – God’s spirit will always be with the Jewish people.

“And as for Me, this is My covenant with them,” God said. “My spirit, which is upon you, and My words that I have placed in your mouth, shall not depart from your mouth, from the mouths of your offspring nor from the mouths of your offspring’s offspring,” God said, “from now and to eternity.”

2.Tanchuma, Noach 3 – God promised that the Oral Torah will never be forgotten by the Jewish people.

God made a covenant with the Jewish people that the Oral Torah would never be forgotten, neither from them nor their descendants until the end of time, as the verse in Yeshaya (59) states, “And as for Me, this is My covenant with them,” said God, “My spirit, which is upon you and My words that I have placed in your mouth, shall never depart [from your mouth nor the mouths of your descendants].” It does not say [only] “from you” but rather “from your mouth nor the mouths of your descendants.”

In order to ensure that the Oral Torah would be kept intact, God promised to guard over it. Nevertheless, as detailed above, the Jewish people themselves established a system of checks and balances to ensure the accurate transmission of the Oral Torah.

Key Themes of Section III.

- Having established that the Written Torah was given with an Oral Torah, we then examined how it is transmitted reliably throughout the generations. How true to the original message has the transmission of the Oral Torah been?

- The Oral Torah was transmitted by the leaders and Sages of each generation with a system of checks and balances: they required Semichah (ordination) before they were allowed to pass on the tradition, they convened yeshivot in every generation to discuss the Oral Torah, and they took notes to make sure nothing would be forgotten or distorted. Furthermore, the Sages were totally committed to this task, understanding the magnitude of their role in transmitting the Oral Torah. Hence, there is no doubt that the Oral Torah we have today is the same as was given by God to Moshe on Sinai.

- The veracity of the Oral Torah currently in our hands is buttressed by cross-referencing its details with Tanach, ancient texts and artifacts.

- Ultimately, if God wants us to observe the Torah and He gave us an Oral Torah by which to do so, it must still be intact – He promised!

Summary Keypoints:

1) How do we know that the Written Law was originally transmitted with an oral component?

There are many proofs to the existence of the Oral Torah. One is the necessity for such a tradition to enable vowelization and punctuation of the Written Torah; these unwritten details affect interpretation, as well. Another area that necessitates the Oral Torah is the internal contradictions within the text itself, which beg for explanation. Additionally, the many unexplained laws and institutions assume the existence of a companion oral tradition.

2) What proof to the existence of the Oral Torah can we find in the text of the Torah itself?

Internal references in the Torah itself refer to an oral tradition containing information not found in the actual text, such as the process of ritual slaughter and the construction of the Mishkan.

3) Why do we have an Oral Torah in the first place? Why didn’t God just give everything in writing?

An oral tradition overcomes the disadvantages of a written text by resolving ambiguity inherent in the text and clarifying the original intent of the Author. At the same time it facilitates the multifaceted reading of the text which itself remains concise yet layered with meaning.

The oral tradition also promotes the teacher-student relationship. This relationship itself leads to further clarity and resolution of ambiguity.

The demands of memorizing an oral tradition ensure that the material is engrained deeply into those who learn it, for it requires more intellectual effort to commit to memory and transmit with personal examples.

The oral tradition safeguards the Torah in the hands of those to whom God gave it in the first place. Other religions have adopted the Written Torah, but only Jews practice the Torah according to its oral tradition. Hence, the Jewish people have been able to preserve their identity throughout the long exile.

4) What proof is there that the Oral Torah was not simply fabricated by the Sages of the Talmud?

The Mishnah and Talmud contain explanations of the mitzvot in the Torah that can be externally verified by verses in Tanach, other ancient manuscripts like the Septuagint, and artifacts and archeological finds of synagogues and mikva’ot.

5) How can we be sure that the Oral Torah remained true to the original intent of the Torah?

The Torah was transmitted from one generation to the next with a checks and balance system that ensured there would be no distortion of the message.

Since the covenant between God and the Jewish people is sealed by virtue of the Oral Torah, we have been promised that it will always be safeguarded. It is the eternal heritage of the Eternal God.

Additional Sources:

The Oral Torah Lectures by Rabbi Dr. Dovid Gottlieb from www.dovidgottlieb.com

The Oral Law by Rabbi Mordechai Becher and A Rational Approach to the Divinity of the Oral Tradition by Rabbi Lawrence Kelemen: www.simpletoremember.com

Rabbi Avraham Edelstein, The Oral Law, www.nerleelef.com/books/orallaw.pdf

Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch (Maharitz) Chajes, Mevo HaTalmud – The Student’s Guide Through the Talmud Maharal, Be’er HaGolah

Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, Handbook of Jewish Thought, Volume 1, Chapters 9 & 12

Rabbi H. Chaim Schimmel, The Oral Torah, Chapter 7

The above article is extracted from www.morashasyllabus.com.